|

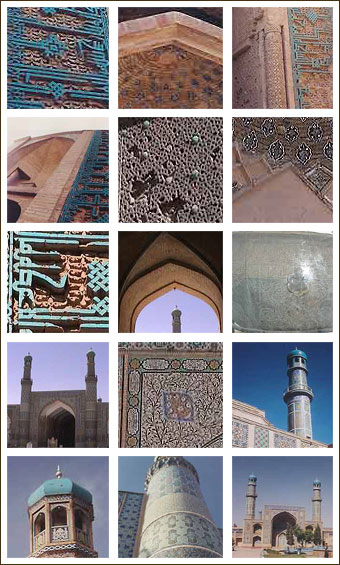

MASJID-E JAMI,

The great mosque of Herat is one of Afghanistan’s

more attractive sights. The form in which it stands today

was originally laid out on the site of an earlier 10th century

mosque in the year 1200 by the Ghrid Sultan Ghiyasuddin. Only

tantalizing fragments of Ghorid decoration remain except for

a splendid portal situated to the south of the main entrance.

(enter from front situated to the south of the main entrance.

(Enter from front garden through small door in mosque wall.)

A bold Kufic inscription, including the name of the monarch,

stands in high Persian-blue relief above a soft buff background

intricately designed with floral motifs in cut brick. The

combination of the bright, bold straight-lined script contrasts

dramatically with the graceful delicacy of the background.

It is an exciting example of the artistic sophistication of

the ghorids. This stunning decoration was hidden under Timurid

decorative tile until the winter of 1964 when experts working

with the Kabul Museum removed the later Timurid decoration

dating from the 15th century. The upper section of the Timurid

arch, lower that the ghorid arch, has been left for interesting

comparisons. Ghorid geometric patterns give way to increasingly

exuberant floral patterns in the timurid decoration; coloured

tile used sparingly only as an accent by the Ghorid is used

to cover every inch of the architectural facade by their successors.

The lavish Timurid decorative restoration covered the entire

surface of the mosque but it disappeared as the unstable political

climate enveloped Herat during the 400 years following Timurid

rule. Photographs taken in the courtyard in the early tears

of the 20th century show only piles of rubble against bleak,

white-washed walls. In 1943 an ambitious restoration program

began and continues to today. It is the creation of three

noted Herati artists, Fikhri Seljuki Herawi, Mohammad Sa’id

Mashal-i Ghori, and the accomplished calligrapher, Mohammad

Ali Herawi. A visit to the mosque workshop (to left of corridor

leading from the front garden into the courtyard) is highly

recommended.

The huge bronze cauldron in the courtyard dates from the reign

of the Kart kings of Herat (1332-1381). It was originally

used as a receptacle fro sherbet (a sweet drink) which was

served to workshipers on feast days. It is now used for donations

for the upkeep of the mosque."

..." Better preserved fragments of Ghorid decoration

may be seen on the arches of the short corridors on either

side of the main iwan where the mehrab (prayer niche) is let

into the west wall. Here the work was executed in cut brick

and molded terracotta. In the south corridor, there is a Kufic

inscription with a floral background done in a distinctive

angular “brambly” style little seen elsewhere.

Above this band there are two large panels of brickwork interspersed

with x-form plugs and bordered with an undulating chain of

molded terracotta arabesques. Simple in concept, the use of

plain unadorned brick for design and texture produces a thoroughly

handsome effect which is both aesthetically pleasing and strong.

Between these brick panels there is a narrower panel filled

with a complicated geometric design formed by a series of

buds and interconnecting tendrils.

All that is left of the splendid Timurid restoration undertaken

by Sultan Husain Baiqara’s prime minister Mir Ali Sher

Nawai in 1498 may be found on the inside of the arcade in

the southwest corner of the courtyard. The interiors fo these

five arches are decorated with narrow strips of blue tile

hexagons and octagons sprinkled with tiny golden flowers.

Plain pink-beige tile plaques slightly in relief fill the

spaces between. The relief and the tiny flowers produce an

illusion of depth and mobility which is extremely effective.”

From Dupree, N. H. An historical guide to Afghanistan. Kabul.

1977. p.250

CONDITION:

Well preserved by the community

|

|

MASJID-E

JAMI

|

|